In March 2009, the Women’s Studies undergraduate program (among others) was cut at Guelph. I wasn’t involved in the issue myself, but knew a few people who rallied against this decision. They cited it as ironic evidence that feminism is far from being a finished movement. At the time, I only saw a superficial link between the Women’s Studies program cut and feminism; I didn’t know what feminism really was.

Now that I am reading ecofeminist literature and gaining an understanding of this environmental philosophy, I am also beginning to really appreciate the feminist philosophy. Both ecofeminism and feminism have far broader impacts than the labels will have you perceive. In fact, they both have significant impacts for ecology and science.

The terms “ecofeminism” and “feminism” tend to put people off. There is a connotation of radical outburst and civil disobedience, reserved for the very passionate and very outraged. While these may be the most visible parts of the movement, at the heart of it is simply a powerful argument about value dualities.

The story begins with two familiar dualities: Male/Female, and Reason/Emotion. The dualities are commonly viewed in parallel, with men being typically associated with reason and thinking, and women with emotion and feeling.

There is nothing inherently wrong with noticing differences and contrasting two things that are different. The problem emerges when we start to value one more than the other. One is seen as superior, the other inferior. It becomes acceptable for one to dominate, control, and use the other. The problem emerges when we start treating the two as oppositional rather than complementary.

This happened to the Reason/Emotion duality, beginning with the advent of Western philosophy and carrying on (largely unnoticed) today. Western philosophy sees reason as the epitome of human existence. Reason is a sophisticated, high-order capacity, keeping us grounded from the whims of “animal” instinct and “mere” emotion. Without reason, we would be no better than our amoral (and inferior) counterparts on Earth–that is, animals. The ability to reason is essentially what defines us as humans.

Ecofeminist Val Plumwood questions this definition:

What is taken to be authentically and characteristically human, defining of the human, as well as the ideal for which humans should strive is not to be found in what is shared with the natural and animal (e.g., the body, sexuality, reproduction, emotionality, the senses, agency) but in what is thought to separate and distinguish them–especially reason and its offshoots. Hence humanity is defined not as part of nature (perhaps a special part) but as separate from and in oposition to it. Thus the relation of humans to nature is treated as an oppositional and value dualism.

Why do we emphasize the traits that distinguish us from animals, but ignore those that we share with animals? Besides being thinking creatures, are we not also bodily creatures and feeling creatures? It is this conception of human, stressing our reason, our separateness from other animals, that breeds another parallel divide: Human/Nature.

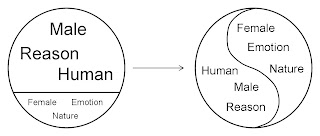

These three dualities (Reason/Emotion, Male/Female, and Human/Nature) are inextricably linked. And ecofeminists assert that Western society’s obsession with reason has created the twin domination of women and nature. Obsession with reason has led us to highly value the “masculine” properties of thinking, distance, and abstraction, while degrading the “feminine” properties of feeling, affection, and experience. This oppressive framework results in the pervasive and subliminal message: nature and women cannot reason (at least not as well as men), therefore it is okay to dominate them.

This makes it okay for men to continually earn higher salaries than women. This makes it okay for humans to continually support animal abuse with every purchase of factory farmed meat. (I don’t mean to fault anyone for what they earn or what they eat; social constructs have allowed for certain habits and conveniences, certain ethics.)

More invisibly, this makes it okay for, say, an ecology professor (probably male, teaching a class of probably mostly females) to heavily embed critical thinking into his curriculum, without any effort to nurture his students’ emotional connection with nature. This makes it okay for, say, an ecologist to publish a paper on riparian buffers and water quality, without addressing (either publicly or privately) the instrumentalisation of forest and trees into “riparian buffers” and water and lake into “water quality”.

Why do ecology students rarely get to go outside? Why are they only asked what they think about some ecosystem, community, or population, never what they feel for a particular place or subject? Why do ecologists study “natural resources” and not nature? (As if nature is only worth what it can provide for us.) Or “wildlife management” and not wildlife? (As if wildlife is ours to control, needing rules imposed on them when they show signs of disobedience.) These are real-world examples of our reason-dominated view, representing the widely accepted (even celebrated) norm in ecology.

Male-biased views entrench our education system, perhaps most blatantly in university science departments. Caring and love are cast aside. Professors, with the best of intentions, teach us that these are “merely” emotions, unreliable and untrustworthy. A good student will channel these passions into something productive and respectable–something rational.

It is not the ecofeminist or feminist’s intention to reduce the prestige of reason in Western society. Rather, they question why this must come at the expense of the prestige of emotion. Reason is undebatably an important and powerful defense against myth, superstition, and propaganda. It allows us to evaluate, reveal, and construct. The “voice of reason” lets us look past individual desires to a more objective stance. Reason can serve as a friendly invitation to explore divergent views.

But emotion has much value, too. Ecofeminists and feminists validate the role of care, compassion, empathy, and inclusivity in our ethics and in our lives. These emotions are undebatably important and powerful antidotes for insensitivity, callousness, and apathy. Emotion, too, allows us to evaluate, reveal, and construct. Heartfelt emotions like sympathy and love carry us back from abstract theory to personal experience. Like reason, emotion can serve as a friendly invitation to explore divergent views.

To be human is to both think and feel. Thinking and feeling are different and complementary modes of knowing. They keep each other in check: thinking pulls us back from irrationality; feeling pulls us back from blind rationality. Western philosophy presents thinking and feeling as at war, with thinking being the favoured winner. Ecofeminism and feminism reject this oppositional value duality. Thinking and feeling feed each other. The complementarity of emotion and reason is our best toolkit for understanding the world and deciding how we ought to live.

The paradox of ecology is that it recognizes the importance of nature and the strain that humans impose on nature. Yet it insists on operating under a reason-dominated framework (i.e. science and the hypothetico-deductive method) that subliminally and continually oppresses nature. To truly value nature (and women), we must first seriously re-consider the oppositional value dualities that have led to this oppression. Borrowing a symbol from Buddhist philosophy, this shift must take place:

Caring and love should not be cast aside. They should be encouraged. I believe this encouragement can and should take place in an ecology classroom, right alongside encouraging critical thought and hypothetico-deductive reasoning. (Perhaps the traditional reason-dominated and male-biased classroom is a fundamental barrier against attracting and keeping women in science…but that is another posting altogether.)

Returning to the issue of the Women’s Studies program at Guelph, it is ironic indeed that a program giving voice to the value of emotion was single-handedly silenced by a reason-dominated institution. At the time, I was hard at work completing my Master of Science degree, writing about “riparian buffers” and “water quality” within the impenetrable walls of the new Science Complex. I had no idea that I, too, was fueling the twin domination of women and nature. I found the loss of Women’s Studies unfortunate, but was largely oblivious to its heavy social implications.

Reading ecofeminist philosophy has really opened my eyes. Ecofeminism is only superficially about stopping animal cruelty and championing for women’s rights. It digs far deeper, revealing the oppositional value dualities that underscore our societal prejudices. This story does not only apply to women and nature, but virtually to every group that has faced discrimination (Aboriginal communities, disabled persons, LGBT, etc.). Ecofeminism sheds light on the shared history and shared challenges of many social and environmental problems.

For me, I am astonished to learn the tight links between social and environmental problems. I am also astonished to learn how much I did not learn in my years of science education. Thus, I am ever more convinced that we need stronger commitment to interdisciplinary education and research. Disconcertingly…guess what other undergraduate program was cut at Guelph in March 2009? Arts and Science.